Ten years from now, primary and secondary education may look more like a scene from Tim Allen's workshop in The Santa Clause than Ben Stein's economics class in Ferris Bueller's Day Off. In some schools, like San Diego's High Tech High, it already does.

Frequently Asked Questions | Understanding the Rankings | Top 10 High Schools | America's Top High Schools | Beating the Odds - Top Schools for Low Income Students | Mapping America's Top High Schools | Newsweek's Top High Schools Special Section

With compact disc chandeliers, a piano whose glass exterior reveals how it works, birds and whales and geometric shapes soaring overhead, a ring of bicycle wheels the size of a clock tower spinning constantly through an intricate pulley system, and dozens of other mechanisms, paintings, sculptures and projects ornamenting every hall and classroom, High Tech High looks something like a cross between a science center and a museum of modern art, where the only thing more jaw-dropping than what's on display is the fact that all of it is created by kids in grades K-12.

High Tech High was founded 14 years ago by a coalition of San Diego business leaders and educators. It has since grown into its own district of charter schools—three elementary, four middle and five high schools, as well as a graduate school of education—where the learning happens mostly through "kids making, doing, building, shaping and inventing stuff," explains CEO and founding Principal Larry Rosenstock. Students spend most of the school day working together on projects that integrate and apply all of the subjects that are traditionally separated in academic settings. "Kindergarten has it right," Rosenstock says, referring to how kindergarteners "experience [education] as a whole," rather than have someone tell them, "OK, now you're going to math. Then you're going to science," etc.

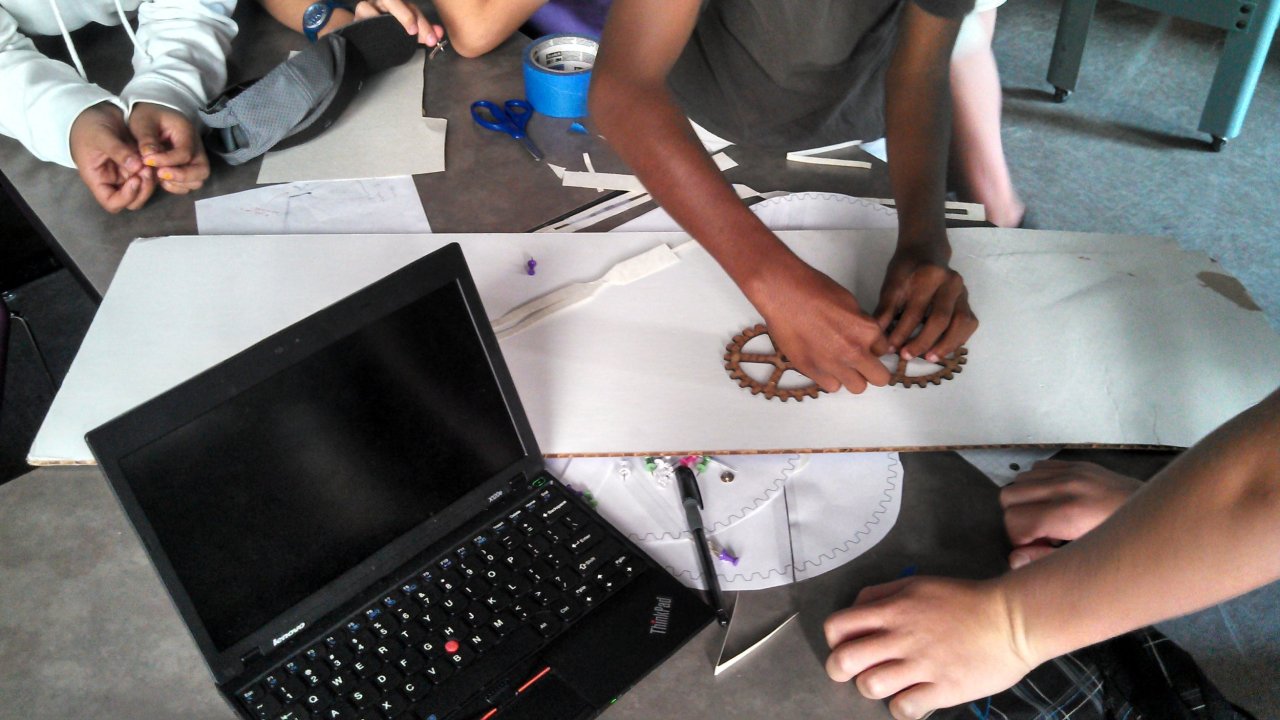

Consider a recent ninth-grade assignment on the rise and fall of populations. Humanities teacher Mike Strong and physics and engineering teacher Scott Swaaley told their group of 50 freshmen to build a 6-foot-diameter geared wheel out of wood and come up with a theory about why and how civilizations rise and fall based on their readings and research on the Mayans, Romans and Greeks. After presenting and defending each of their theories, they worked in teams of five to figure out a way to physically manifest those abstract concepts in the form of a mechanism to be affixed to and powered by the turning of the class's giant wheel. The result was mesmerizing—a wooden piece of art composed of dozens of gears of varying shapes and sizes, turning in different directions around laser-printed text and illustrations, and a rotating wheel etched with student drawings.

Before it was mounted on the wall of a conference room where visitors now gawk at it, the rise and fall of populations project was displayed at High Tech High's annual exhibition of student learning, a two-night event that is open to the public and attracts thousands each spring. The event features the work of elementary, middle and high schoolers from all the campuses. According to the school's website, "Past exhibitions have included a World War I–era restaurant and cabaret, an art gallery, a museum-like exhibit on the history and physics of baseball, [and] simulations of faraway ecologies."

Adrian, a student and guitarist who chose to build an amp for his project, says that he enjoys exhibition because he loves showing everyone "the process I went through [and] the work I put into it.… I think it's fun when you make something you're really proud of and other people are interested in it and give you compliments." That is precisely the idea behind these exhibitions—to make work fun, public and something in which students take pride. "When kids have that feeling, it's transformative for them," says Rosenstock.

Tony Wagner, current expert in residence at Harvard University's new Innovation Lab, and the founder of Harvard's Change Leadership Group, calls High Tech High his "favorite school" and says of what goes on there, "That's the future." According to Wagner, the idea of school as a place where knowledge is transferred from teacher to student, whose success is measured by the accuracy of his/her regurgitation of it, is antiquated. This instructional model does not foster what Wagner believes is the most essential skill in today's world: the ability to innovate.

In his most recent book, Creating Innovators: The Making of Young People Who Will Change the World, Wagner profiles some of America's great innovators and observes a pattern in their youths: A childhood of creative play led to their development of deep-seated interests and curiosities, and these passions fueled their intrinsic motivation to set and achieve career and life goals. Another trend Wagner found was that the adults in these innovators' young lives nurtured their imaginations and taught them to persevere and learn from failure. "What we're learning about innovation," says Wagner, "is the importance of failing early and failing often...failing forward, failing fast and cheap. The whole idea of trial and error is something that is antithetical to our formal systems of education.… In fact, we penalize failure.… So there's a complete contradiction between the world of schooling and the world of innovation."

THE MAKER MOVEMENT is a global community of inventors, designers, engineers, artists, programmers, hackers, tinkerers, craftsmen and DIY'ers—the kind of people who share a quality that Rosenstock says "leads to learning [and]…to innovation," a perennial curiosity "about how they could do it better the next time." The design cycle is all about reiteration, trying something again and again until it works, and then, once it works, making it better. As manufacturing tools continue to become better, cheaper and more accessible, the Maker Movement is gaining momentum at an unprecedented rate. Over the past few years, so-called "makerspaces" have cropped up in cities and small towns worldwide—often in affiliation with libraries, museums and other community centers, as well as in public and independent schools—giving more people of all ages access to mentorship, programs and tools like 3-D printers and scanners, laser cutters, microcontrollers and design software.

At schools with makerspaces, students are already starting to follow the pattern that Wagner observes among young innovators. Henry Simonoff, a ninth-grader at St. Ann's School in the Brooklyn Heights neighborhood of New York City, is one such example. The summer after sixth grade, Simonoff went to a St. Ann's computer camp, where his teacher, Lizbeth Arum, taught him how to model and make electronics cases using the 3-D design Web app Tinkercad. He discovered that he loved designing, so the following school year he took a 3-D printing elective and began experimenting with his own ideas. However, 3-D printing is a slow process, and the MakerBots in the classroom couldn't keep up with Simonoff and his classmates' creative demand.

"I finally decided I could take on much bigger and more ambitious projects if I got one for myself," he says. So he sold his laptop on eBay, added to those proceeds all of the birthday money and allowance he had saved over the years, and took out a loan from the Bank of Dad to buy the cheapest 3-D printer he could find online. By the end of seventh grade, he had paid his father back entirely—all from the sales of his customized iPhone cases and little cone toys that he'd designed to flip around like benign butterfly knives. Once his debt was paid, he could finally begin the more ambitious project he'd had in mind: "the zero point energy field manipulator," or gravity gun, from the video game Half-Life 2. He designed and built a full-size model of it—3 feet long and 2 feet high—"which was pretty difficult," he explains, "because the actual platform of the machine is 10 inches by 10 inches," so he had to get creative. "It pretty much broke down my printer," he says, "but I fixed it." Simonoff's current project—"the sky hook" from the game BioShock Infinite—is an "even more ambitious" endeavor than the gravity gun, "because it has a lot of moving parts, gears, etc." He says it keeps falling apart, but he's not discouraged. "This is really…my passion," he says.

It's not just private school kids who are using this technology. Public schools are also beginning to experiment. Albemarle County Public Schools, for example, a 27-school district serving nearly 13,000 students in the area surrounding Charlottesville, Virginia, is developing classes like the one Simonoff took at St. Ann's and assignments like the giant wheel project at High Tech High. The superintendent of Albemarle County Public Schools, Pam Moran, says many of her students are beginning to "see themselves as designers, makers." She says they're now "constantly looking at the world in terms of problems that they can solve." Moran tells an anecdote about one of her high schoolers, who noticed that a screw was missing from the couch in the library and rushed to the librarian to tell her that he could fix it. The student removed another screw to get the dimensions of the one that was missing and came back later that week with an exact copy he'd designed and 3-D printed, which he then used to fix the couch.

Moran says her district's goal is to create experiences for its students that "make learning so powerful and memorable" that they'll seek out those types of experiences post-graduation. Her teaching staff at Sutherland Middle School recently came up with an eighth-grade assignment at a time when, in science, the students were learning about electricity; in history, they were studying 19th century America; and in computer science and engineering, they were 3-D modeling. The teachers of all three subjects came together with the idea of having the kids build Vail telegraphs using 3-D-designed-and-printed parts. After completing the project, an eighth grader named Jennifer said, "We…really understand electricity much better than we would if, say, we just made an electromagnet and started picking up paper clips. It's just easier to understand something if it's right in front of you and you can do different things to it—and see the reactions."

She and another student, Nate, gave a technical explanation of how the telegraph functions when the students presented their project at the Smithsonian museum in Washington, D.C. They also discussed the historical context—"like during the Civil War," Jennifer explained, "they needed relays, so if the electricity were to burn out, the relay would keep the fresh electricity going." After the presentation, the kids set up one telegraph at their middle school and another at the elementary school to communicate between the two with the help of a smartphone app that translates Morse code. In addition to being a fun activity, this put the students in the shoes of the people they were studying in history. "I learn better when I'm experiencing it," says Jennifer.

While this kind of education does result in the gain of measurable, practical skills, "it's really about the problem-solving skills as opposed to the specific [technical] skills," says David Wells, manager of creative making and learning at the New York Hall of Science. It's about teaching kids how to break down their big ideas into smaller components in order to figure out a plausible first step. It's about helping students become familiar not just with makerspace tools but, more important, with the process of finding, accessing and using information to teach themselves how to do whatever it is they want to do, and make whatever they want to make.

As Wells says, "We're developing the 'I can' mentality."